The OPERA project¶

From the OPERA (Observational Products for End-Users from Remote Sensing Analysis) project:

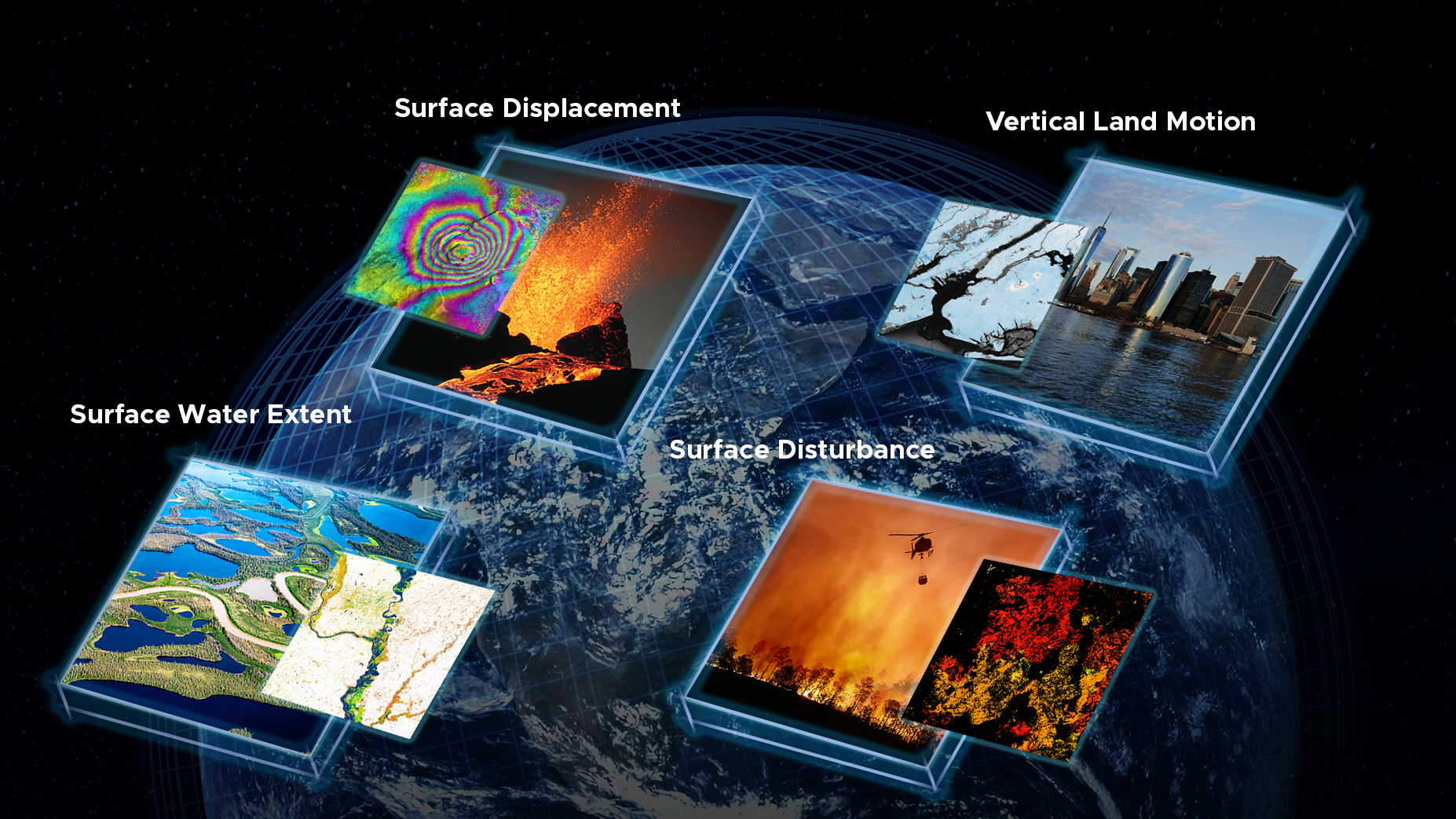

Started in April 2021, the Observational Products for End-Users from Remote Sensing Analysis (OPERA) project at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory collects data from satellite radar and optical instruments to generate six product suites:

- a near-global Surface Water Extent product suite

- a near-global Surface Disturbance product suite

- a near-global Radiometric Terrain Corrected product

- a North America Coregistered Single Look complex product suite

- a North America Displacement product suite

- a North America Vertical Land Motion product suite

That is, OPERA is a NASA initiative that takes, e.g., optical or radar remote-sensing data gathered from satellites and produces a variety of pre-processed data sets for public use. OPERA products are not raw satellite images; they are the result of algorithmic classification to determine, e.g., which land regions contain water or where vegetation has been displaced. The raw satellite images are collected from measurements made by the instruments onboard the Sentinel-1 A/B, Sentinel-2 A/B, and Landsat-8/9 satellite missions (hence the term HLS for “Harmonized Landsat-Sentinel” in numerous product descriptions).

The OPERA Land Surface Disturbance (DIST) product¶

One of the OPERA data products is the Land Surface Disturbance (DIST) product (more fully described in the OPERA DIST HLS product specification). The DIST products map vegetation disturbance (specifically, vegetation cover loss per HLS pixel whenever there is an indicated decrease) from Harmonized Landsat-8 and Sentinel-2 A/B (HLS) scenes. One application of this data is to quantify damage due to wildfires in forests. The DIST_ALERT product is released at regular intervals (the same cadence of HLS imagery, roughly every 12 days over a given tile/region); the DIST_ANN product summarizes disturbance measurements over a year.

The DIST products quantify surface reflectance (SR) data acquired from the Operational Land Imager (OLI) aboard the Landsat-8 remote sensing satellite and the Multi-Spectral Instrument (MSI) aboard the Sentinel-2 A/B remote-sensing satellite. The HLS DIST data products are raster data files, each associated with tiles of the Earth’s surface. Each tile is represented using projected map coordinates aligned with the Military Grid Reference System (MGRS). Each tile is divided into 3,660 rows and 3,660 columns at 30 meter pixel spacing (so a tile is long on each side). Neighboring tiles overlap by 4,900 meters in each direction (the details are fully described in the DIST product specification).

The OPERA DIST products are distributed as Cloud Optimized GeoTIFFs; in practice, this means that different bands are stored in distinct TIFF files. The TIFF specification does permit storage of multidimensional arrays in a single file; storing distinct bands in distinct TIFF files allows files to be downloaded independently.

Band 1: Maximum Vegetation Loss Anomaly Value (VEG_ANOM_MAX)¶

Let’s examine a local file with an example of DIST-ALERT data. The file contains the first band of disturbance data: the maximum vegetation loss anomaly. For each pixel, this is a value between 0% and 100% representing the percentage difference between current observed vegetation cover and a historical reference value. That is, a value of 100 corresponds to complete loss of vegetation within a pixel and a value of 0 corresponds to no loss of vegetation. The pixel values are stored as 8-bit unsigned integers (UInt8) because the pixel values need only range between 0 and 100. A pixel value of 255 indicates missing data, i.e., the HLS data was unable to determine a maximum vegetation anomaly value for that pixel. Of course, using 8-bit unsigned integer data is a lot more efficient for storage and for transmitting data across a network (as compared to, e.g., 32- or 64-bit floating-point data).

Let’s begin by importing the required libraries. Notice we’re also pulling in the FixedTicker class from the Bokeh library to make interactive plots a little nicer.

# Notebook dependencies

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

from pathlib import Path

import rioxarray as rio

import geoviews as gv

gv.extension('bokeh')

import hvplot.xarray

from bokeh.models import FixedTickerWe’ll read the data from a local file 'OPERA_L3_DIST-ALERT-HLS_T10TEM_20220815T185931Z_20220817T153514Z_S2A_30_v0.1_VEG-ANOM-MAX.tif'. Before loading the data, let’s examine the metadata embedded in the filename.

LOCAL_PATH = Path.cwd().parent / 'assets' / 'OPERA_L3_DIST-ALERT-HLS_T10TEM_20220815T185931Z_20220817T153514Z_S2A_30_v0.1_VEG-ANOM-MAX.tif'

filename = LOCAL_PATH.name

print(filename)This rather long filename consists of several fields separated by underscore (_) characters. We can use the Python str.split method to view the distinct fields more easily.

filename.split('_') # Use the Python str.split method to view the distinct fields more easily.OPERA product files have a particular naming scheme (as described in the DIST product specification). In the output above, we can extract certain metadata for this example:

- Product:

OPERA; - Level:

L3; - ProductType:

DIST-ALERT-HLS; - TileID:

T10TEM(string referencing a tile of the Military Grid Reference System (MGRS)); - AcquisitionDateTime:

20220815T185931Z(string representing a GMT time-stamp for the data acquisition); - ProductionDateTime :

20220817T153514Z(string representing a GMT time-stamp for when the data product was produced); - Sensor:

S2A(identifier of the satellite that acquired the raw data:L8(Landsat-8),S2A(Sentinel-2 A) , orS2B(Sentinel-2 B); - Resolution:

30(i.e., pixels of sidelength ); - ProductVersion:

v0.1; and - LayerName:

VEG-ANOM-MAX

Notice that naming conventions like this one are used by NASA’s Earthdata Search to pull data meaningfully from SpatioTemporal Asset Catalogs (STACs). Later on, we’ll use these fields—in particular the TileID & LayerName fields—to filter search results before retrieving remote data.

Let’s load the data from this local file into an Xarray DataArray using rioxarray.open_rasterio. We’ll do some relabelling to label the coordinates appropriately and we’ll extract the CRS (coordinate reference system).

data = rio.open_rasterio(LOCAL_PATH)

crs = data.rio.crs

data = data.rename({'x':'longitude', 'y':'latitude', 'band':'band'}).squeeze()datacrsBefore generating a plot, let’s create a basemap using ESRI tiles.

# Creates basemap

base = gv.tile_sources.ESRI.opts(width=750, height=750, padding=0.1)We’ll also use dictionaries to capture the bulk of the plotting options we’ll use in conjunction with .hvplot.image later on.

image_opts = dict(

x='longitude',

y='latitude',

rasterize=True,

dynamic=True,

frame_width=500,

frame_height=500,

aspect='equal',

cmap='hot_r',

clim=(0, 100),

alpha=0.8

)

layout_opts = dict(

xlabel='Longitude',

ylabel='Latitude'

)Finally, we’ll use the DataArray.where method to filter out missing pixels and the pixels that saw no change in vegetation; these pixel values will be reassigned as nan so they will be transparent when the raster is plotted. We’ll also modify the options in image_opts and layout_opts slightly.

veg_anom_max = data.where((data>0) & (data!=255))

image_opts.update(crs=data.rio.crs)

layout_opts.update(title=f"VEG_ANOM_MAX")These changes allow us to generate a meaningful plot.

veg_anom_max.hvplot.image(**image_opts).opts(**layout_opts) * baseIn the resulting plot, the white and yellow pixels correspond to regions in which some deforestation has occurred, but not much. By contrast, the darker red, orange, and black pixels correspond to regions that have lost significantly more or almost all vegetation.

Band 2: Date of Initial Vegetation Disturbance (VEG_DIST_DATE)¶

The DIST-ALERT products contain several bands (as summarized in the DIST product specification). The second band we’ll examine is the date of initial vegetation disturbance within the last year. This is stored as a 16-bit integer (Int16).

The file OPERA_L3_DIST-ALERT-HLS_T10TEM_20220815T185931Z_20220817T153514Z_S2A_30_v0.1_VEG-DIST-DATE.tif is stored locally. The DIST product specification describes how to file-naming conventions used; notable here is the acquisition date & time 20220815T185931, i.e., almost 7pm (UTC) on August 15th, 2022.

We’ll load and relabel the DataArray as before.

LOCAL_PATH = Path.cwd().parent / 'assets' / 'OPERA_L3_DIST-ALERT-HLS_T10TEM_20220815T185931Z_20220817T153514Z_S2A_30_v0.1_VEG-DIST-DATE.tif'

data = rio.open_rasterio(LOCAL_PATH)

data = data.rename({'x':'longitude', 'y':'latitude', 'band':'band'}).squeeze()In this particular band, the value 0 indicates no disturbance in the last year and -1 is a sentinel value indicating missing data. Any positive value is the number of days since Dec. 31, 2020 in which the first disturbance is measured in that pixel. We’ll filter out the non-positive values and preserve these meaningful values using DataArray.where.

veg_dist_date = data.where(data>0)Let’s examine the range of numerical values in veg_dist_date using DataArray.min and DataArray.max. Both of these methods will ignore pixels containing nan (“Not-a-Number”) when computing the minimum and maximum.

d_min, d_max = int(veg_dist_date.min().item()), int(veg_dist_date.max().item())

print(f'{d_min=}\t{d_max=}')In this instance, the meaningful data lies between 247 and 592. Remember, this is the number of days elapsed since Dec. 31, 2020 when the first disturbance was observed in the last year. Since this data was acquired on Aug. 15, 2022, the only possible values would be between 227 and 592 days. So we need to recalibrate the colormap in the plot

image_opts.update(

clim=(d_min,d_max),

crs=data.rio.crs

)

layout_opts.update(title=f"VEG_DIST_DATE")veg_dist_date.hvplot.image(**image_opts).opts(**layout_opts) * baseWith this colormap, the lightest pixels showed some signs of deforestation close to a year ago. By contrast, the black pixels first showed deforestation close to the time of data acquisition. This band, then, is useful for tracking the progress of wildfires as they sweep across forests.

Band 3: Vegetation Disturbance Status (VEG_DIST_STATUS)¶

Finally, let’s take a look at a third band from the DIST-ALERT data product family, namely the vegetation disturbance status. These pixel values are stored as 8-bit unsigned integers; there are only 6 distinct values stored:

- 0: No disturbance

- 1: Provisional (first detection) disturbance with vegetation cover change <50%

- 2: Confirmed (recurrent detection) disturbance with vegetation cover change < 50%

- 3: Provisional disturbance with vegetation cover change ≥ 50%

- 4: Confirmed disturbance with vegetation cover change ≥ 50%

- 255: Missing data

A pixel value is flagged provisionally changed when the vegetation cover loss (disturbance) is first observed by a satellite; if the change is noticed again in subsequent HLS acquisitions over that pixel, then the pixel is flagged as confirmed.

We can use a local file as an example of this particular layer/band of the DIST-ALERT data. The code is the same as above, but do observe:

- the data filtered reflects the meaning pixel values for this layer (i.e.,

data>0anddata<5); and - the limits on the colormap are reassigned accordingly (i.e., from 0 to 4).

Notice the use of the FixedTicker in defining a colorbar better suited for a discrete (i.e., categorical) colormap.

LOCAL_PATH = Path.cwd().parent / 'assets' / 'OPERA_L3_DIST-ALERT-HLS_T10TEM_20220815T185931Z_20220817T153514Z_S2A_30_v0.1_VEG-DIST-STATUS.tif'

data = rio.open_rasterio(LOCAL_PATH)

data = data.rename({'x':'longitude', 'y':'latitude', 'band':'band'}).squeeze()veg_dist_status = data.where((data>0)&(data<5))

image_opts.update(crs=data.rio.crs)layout_opts.update(

title=f"VEG_DIST_STATUS",

clim=(0,4),

colorbar_opts={'ticker': FixedTicker(ticks=[0, 1, 2, 3, 4])}

)veg_dist_status.hvplot.image(**image_opts).opts(**layout_opts) * baseThis continuous colormap does not highlight the features in this plot particularly well. A better choice would be a categorical colormap. We’ll see how to achieve this in the next notebook (with the OPERA DSWx data products).