From the OPERA (Observational Products for End-Users from Remote Sensing Analysis) project:

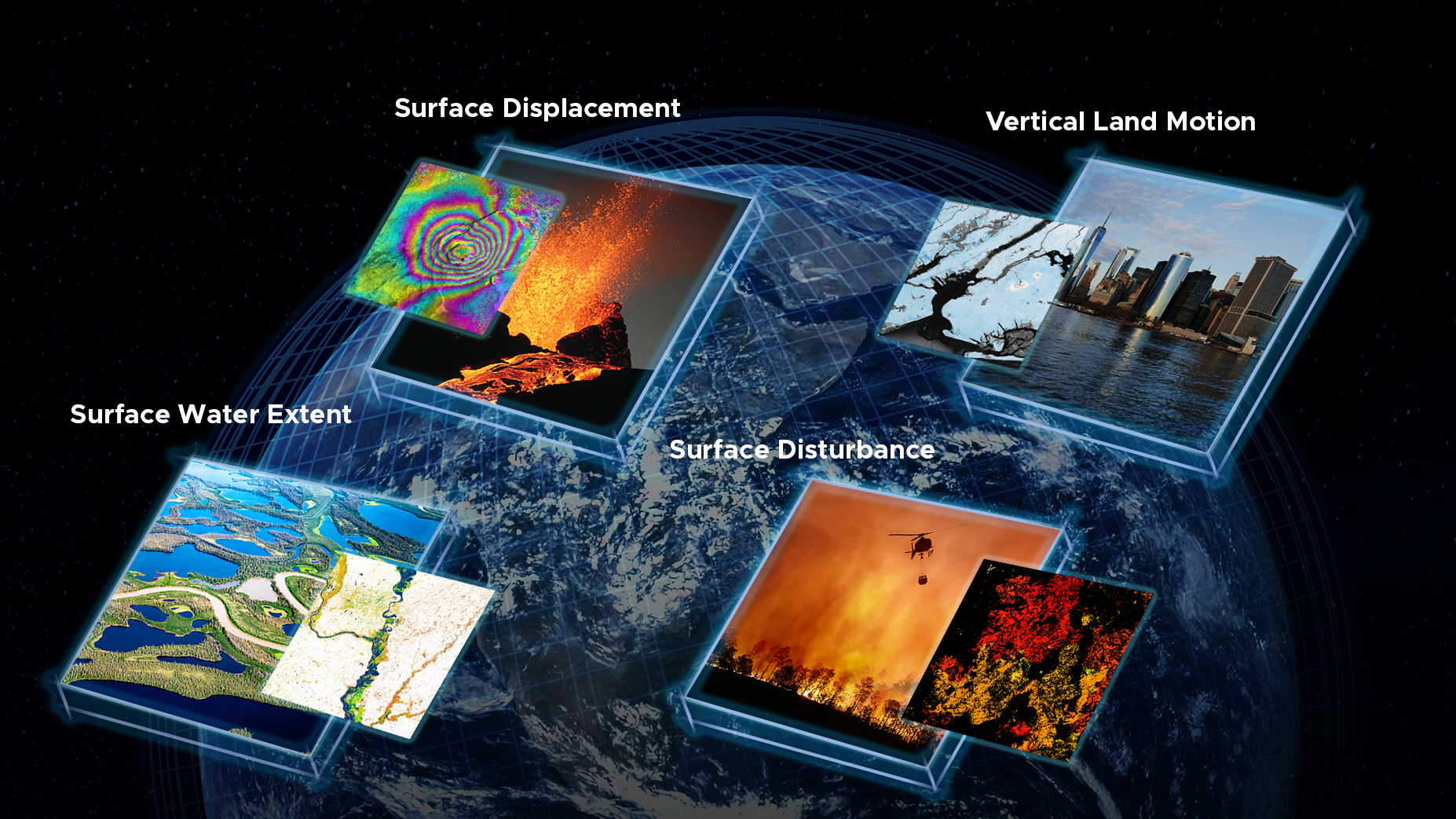

Started in April 2021, the Observational Products for End-Users from Remote Sensing Analysis (OPERA) project at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory collects data from satellite radar and optical instruments to generate six product suites:

- a near-global Surface Water Extent product suite

- a near-global Surface Disturbance product suite

- a near-global Radiometric Terrain Corrected product

- a North America Coregistered Single Look complex product suite

- a North America Displacement product suite

- a North America Vertical Land Motion product suite

That is, OPERA is a NASA initiative that takes, e.g., optical or radar remote-sensing data gathered from satellites and produces a variety of pre-processed data sets for public use. OPERA products are not raw satellite images; they are the result of algorithmic classification to determine, e.g., which land regions contain water or where vegetation has been displaced. The raw satellite images are collected from measurements made by the instruments onboard the Sentinel-1 A/B, Sentinel-2 A/B, and Landsat-8/9 satellite missions (hence the term HLS for “Harmonized Landsat-Sentinel” in numerous product descriptions).

The OPERA Dynamic Surface Water Extent (DSWx) product¶

We’ve already looked at the DIST (i.e., land surface disturbance) family of OPERA data products. In this notebook, we’ll examine another OPERA data product: the Dynamic Surface Water Extent (DSWx) product. This data product summarizes the extent of inland water (i.e., water on land masses as opposed to part of an ocean) that can be used to track flooding and drought events. The DSWx product is fully described in the OPERA DSWx HLS product specification.

The DSWx data products are generated from HLS surface reflectance (SR) measurements; specifically, these are made by the Operational Land Imager (OLI) aboard the Landsat 8 satellite, the Operational Land Imager 2 (OLI-2) aboard the Landsat 9 satellite, and the MultiSpectral Instrument (MSI) aboard the Sentinel-2A/B satellites. As with the DIST products, the DSWx products consist of raster data stored in GeoTIFF format using the Military Grid Reference System (MGRS) (the details are fully described in the DSWx product specification). Again, the OPERA DSWx products are distributed as Cloud Optimized GeoTIFFs storing different bands/layers in distinct TIFF files.

Band 1: Water classification (WTR)¶

There are ten bands or layers associated with the DSWx data product. In this tutorial, we will focus strictly on the first band—the water classification (WTR) layer—but details of all the bands are given in the DSWx product specification. For instance, band 3 is the Confidence (CONF) layer that provides, for each pixel, quantitative values describing the degree of confidence in the categories given in band 1 (the Water classification layer). Band 4 is a Diagnostic (DIAG) layer that encodes, for each pixel, which of five tests were positive in deriving the corresponding pixel value in the CONF layer.

The water classification layer consists of unsigned 8-bit integer raster data (UInt8) meant to represent whether a pixel contains inland water (e.g., part of a reservoir, a lake, a river, etc., but not water associated with the open ocean). The values in this raster layer are computed from raw images acquired by the satellite with pixels being assigned one of 7 positive integer values; we’ll examine these below.

Examining an example WTR layer¶

Let’s begin by importing the required libraries and loading a suitable file into an Xarray DataArray. The file in question contains raster data pertinent to the Lake Powell reservoir on the Colorado River in the United States.

import warnings

warnings.filterwarnings('ignore')

from pathlib import Path

import numpy as np, pandas as pd, xarray as xr

import rioxarray as rioimport hvplot.pandas, hvplot.xarray

import geoviews as gv

gv.extension('bokeh')

from bokeh.models import FixedTickerLOCAL_PATH = Path.cwd().parent / 'assets' / 'OPERA_L3_DSWx-HLS_T12SVG_20230411T180222Z_20230414T030945Z_L8_30_v1.0_B01_WTR.tif'

b01_wtr = rio.open_rasterio(LOCAL_PATH).rename({'x':'longitude', 'y':'latitude'}).squeeze()Remember, using the repr for b01_wtr in this Jupyter notebook is quite convenient.

- By expanding the

Attributestab, we can see all the metadata associated with the data acquired. - By expanding the

Coordinatestab, we can examine all the associated arrays of coordinate values.

# Examine data

b01_wtrLet’s examine the distribution of pixel values in b01_wtr using the Pandas Series.value_counts method.

counts = pd.Series(b01_wtr.values.flatten()).value_counts().sort_index()

display(counts)These pixel values are categorical data. Specifically, the valid pixel values and their meanings—according to the DSWx product specification—are as follows:

- 0: Not Water—any area with valid reflectance data that is not from one of the other allowable categories (open water, partial surface water, snow/ice, cloud/cloud shadow, or ocean masked).

- 1: Open Water—any pixel that is entirely water unobstructed to the sensor, including obstructions by vegetation, terrain, and buildings.

- 2: Partial Surface Water—an area that is at least 50% and less than 100% open water (e.g., inundated sinkholes, floating vegetation, and pixels bisected by coastlines).

- 252: Snow/Ice.

- 253: Cloud or Cloud Shadow—an area obscured by or adjacent to cloud or cloud shadow.

- 254: Ocean Masked—an area identified as ocean using a shoreline database with an added margin.

- 255: Fill value (missing data).

Producing an initial plot¶

Let’s make a first rough plot of the raster data using hvplot.image. As usual, we instantiate a view object that slices a smaller subset of pixels to make the image render quickly.

image_opts = dict(

x='longitude',

y='latitude',

rasterize=True,

dynamic=True,

project=True

)

layout_opts = dict(

xlabel='Longitude',

ylabel='Latitude',

aspect='equal',

)

steps = 100

subset = slice(0, None, steps)

view = b01_wtr.isel(longitude=subset, latitude=subset)

view.hvplot.image(**image_opts).opts(**layout_opts)The default colormap does not reveal the raster features very well. Also, notice that the colorbar axis covers the numerical range from 0 to 255 (approximately) even though most of those pixel values (i.e., from 3 to 251) do not actually occur in the data. Annotating a raster image of categorical data with a legend may make more sense than using a colorbar. However, at present, hvplot.image does not support using a legend. So, for this tutorial, we’ll stick to using a colorbar. Before assigning a colormap and appropriate labels for the colorbar, it makes sense to clean up the pixel values.

Reassigning pixel values¶

We want to reassign the raster pixel values to a tighter range (i.e., from 0 to 5 instead of from 0 to 255) to make a sensible colorbar. To do this, we’ll start by copying the values from the DataArray b01_wtr into another DataArray new_data and by creating an array values to hold the full range of permissible pixel values.

new_data = b01_wtr.copy(deep=True)

values = np.array([0, 1, 2, 252, 253, 254, 255], dtype=np.uint8)

print(values)We first need to decide how to treat missing data, i.e., pixels with the value 255 in this raster. Let’s choose to treat the missing data pixels the same as the "Not water" pixels. We can use the DataArray.where method to reassign pixels with value null_val (i.e., 255 in the code cell below) to the replacement value transparent_val (i.e., 0 in this case). Anticipating that we’ll embed this code in a function later, we embed the computation in an if-block conditioned on a boolean value replace_null.

null_val = 255

transparent_val = 0

replace_null = True

if replace_null:

new_data = new_data.where(new_data!=null_val, other=transparent_val)

values = values[np.where(values!=null_val)]

print(np.unique(new_data.values))Notice that values no longer includes null_val. Next, instantiate an array new_values to store the replacement pixel values.

n_values = len(values)

start_val = 0

new_values = np.arange(start=start_val, stop=start_val+n_values, dtype=values.dtype)

assert transparent_val in new_values, f"{transparent_val=} not in {new_values}"

print(values)

print(new_values)Now we combine values and new_values into a dictionary relabel and use the dictionary to modify the entries of new_data.

relabel = dict(zip(values, new_values))

for old, new in relabel.items():

if new==old: continue

new_data = new_data.where(new_data!=old, other=new)We can encapsulate the logic of the preceding cells into a utility function relabel_pixels that condenses a broad range of categorical pixel values into a tighter one that will display better with a colormap.

# utility to remap pixel values to a sequence of contiguous integers

def relabel_pixels(data, values, null_val=255, transparent_val=0, replace_null=True, start=0):

"""

This function accepts a DataArray with a finite number of categorical values as entries.

It reassigns the pixel labels to a sequence of consecutive integers starting from start.

data: Xarray DataArray with finitely many categories in its array of values.

null_val: (default 255) Pixel value used to flag missing data and/or exceptions.

transparent_val: (default 0) Pixel value that will be fully transparent when rendered.

replace_null: (default True) Maps null_value->transparent_value everywhere in data.

start: (default 0) starting range of consecutive integer values for new labels.

The values returned are:

new_data: Xarray DataArray containing pixels with new values

relabel: dictionary associating old pixel values with new pixel values

"""

new_data = data.copy(deep=True)

if values:

values = np.sort(np.array(values, dtype=np.uint8))

else:

values = np.sort(np.unique(data.values.flatten()))

if replace_null:

new_data = new_data.where(new_data!=null_val, other=transparent_val)

values = values[np.where(values!=null_val)]

n_values = len(values)

new_values = np.arange(start=start, stop=start+n_values, dtype=values.dtype)

assert transparent_val in new_values, f"{transparent_val=} not in {new_values}"

relabel = dict(zip(values, new_values))

for old, new in relabel.items():

if new==old: continue

new_data = new_data.where(new_data!=old, other=new)

return new_data, relabelLet’s apply the function just defined to b01_wtr and verify that the pixel values have been changed as desired.

values = [0, 1, 2, 252, 253, 254, 255]

print(f"Before applying relabel_pixels: {np.unique(b01_wtr.values)}")

print(f"Original pixel values expected: {values}")

b01_wtr, relabel = relabel_pixels(b01_wtr, values=values)

print(f"After applying relabel_pixels: {np.unique(b01_wtr.values)}")Notice that the pixel value 5 does not occur in the relabelled array because the pixel value 254 (for “Ocean Masked” pixels) does not occur in the original GeoTIFF file. This is fine; the code writen below will still produce the full range of possible pixel values (& colors) in its colorbar.

Defining a colormap & plotting with a colorbar¶

We are now ready to define a colormap. We define the dictionary COLORS so that the pixel labels from new_values are the dictionary keys and some RGBA color tuples used frequently for this kind of data are the dictionary values. We’ll use variants of the code in the cell below to update layout_opts so that plots generated for various layers/bands from the DSWx data products have suitable legends.

COLORS = {

0: (255, 255, 255, 0.0), # No Water

1: (0, 0, 255, 1.0), # Open Water

2: (180, 213, 244, 1.0), # Partial Surface Water

3: ( 0, 255, 255, 1.0), # Snow/Ice

4: (175, 175, 175, 1.0), # Cloud/Cloud Shadow

5: ( 0, 0, 127, 0.5), # Ocean Masked

}

c_labels = ["No Water", "Open Water", "Partial Surface Water", "Snow/Ice", "Cloud/Cloud Shadow", "Ocean Masked"]

c_ticks = list(COLORS.keys())

limits = (c_ticks[0]-0.5, c_ticks[-1]+0.5)

print(c_ticks)

print(c_labels)To use this colormap, these ticks, and these labels in a colorbar, we create a ditionary c_bar_opts that holds the objects to pass to the Bokeh rendering engine.

c_bar_opts = dict( ticker=FixedTicker(ticks=c_ticks),

major_label_overrides=dict(zip(c_ticks, c_labels)),

major_tick_line_width=0, )We need to update the dictionaries image_opts and layout_opts to include the data relevant to the colormap.

image_opts.update({ 'cmap': list(COLORS.values()),

'clim': limits,

'colorbar': True

})

layout_opts.update(dict(title='B01_WTR', colorbar_opts=c_bar_opts))Finally, we can render a quick plot to make sure that the colorbar is produced with suitable labels.

steps = 100

subset = slice(0, None, steps)

view = b01_wtr.isel(longitude=subset, latitude=subset)

view.hvplot.image( **image_opts).opts(frame_width=500, frame_height=500, **layout_opts)Finally, we can define a basemap, this time using tiles from ESRI. This time, we’ll plot plot the raster at full resolution (i.e., we won’t bother using isel to select a lower-resolution slice from the raster first).

# Creates basemap

base = gv.tile_sources.EsriTerrain.opts(padding=0.1, alpha=0.25)

b01_wtr.hvplot(**image_opts).opts(**layout_opts) * baseThis notebook provides an overview of how to visualize data extracted from OPERA DSWx data products that are stored locally. We’re now ready to automate the search for such products in the cloud using the PySTAC API.