Introduction¶

In a conventional journey to learn about the Physical universe, most physicists are initially presented with evidence that the photon has particle-like properties. One of the suprising facts that Physicists subsequently encounter is that photons are massless. Photons are one of several spin-1 gauge boson particles, alongside gluons and W bosons. Gauge Theory predicts that all gauge bosons have zero mass. Whilst this is observed to be the case for photons, we know that the W boson has mass!

Explaining why the photon is massless and the W boson is massive was a difficult challenge in contemporary physics until the proposal of the Higgs mechanism. Introduced by three different groups in 1964, the Higgs mechanism introduced a new quantum field (the Higgs field) that furnishes W and Z gauge bosons with mass through interactions with the field.

Prior to the invention of the Higgs mechanism, it was not known how to formulate a consistent relativistic field theory with a local symmetry which could contain both massless and massive force carriers.

In addition, the mechanism yields a massive (spin-zero) scalar boson termed the Higgs boson, whose mass is derived from excitations of that field. It is this particle, through its unique decay signature, that was postulated as a candidate for experimental proof of the Higgs mechanism. In 2012, the Higgs boson was discovered independently by the Compact Muon Solenoid and ATLAS experiments at the Large Hadron Collider, with a subsequent confidence of over 5 sigma — that the observed result lies more than five standard deviations (of the measurement) away from the “null hypothesis”.

Five sigma is considered the “gold standard” in particle physics because it guarantees an extremely low likelihood of a claim being false.

Figure 1:Diagram of normal distribution probability density function, Ainali, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://

Decay Modes¶

In the LHC, particles formed in the high energy proton-proton collisions decay almost immediately to smaller (elementary) particles. Consequently, experimentalists tend not to detect these progenitor particles, but rather observe their decay products. Through kinematic reconstruction (measuring the energy and momentum of the entire system of particles), Physicists can look backwards in time to the moment of the collision itself, and learn about what took place (see Figure 2).

Figure 2:Interactive display of an event recorded by the CMS detector in 2018, taken from https://

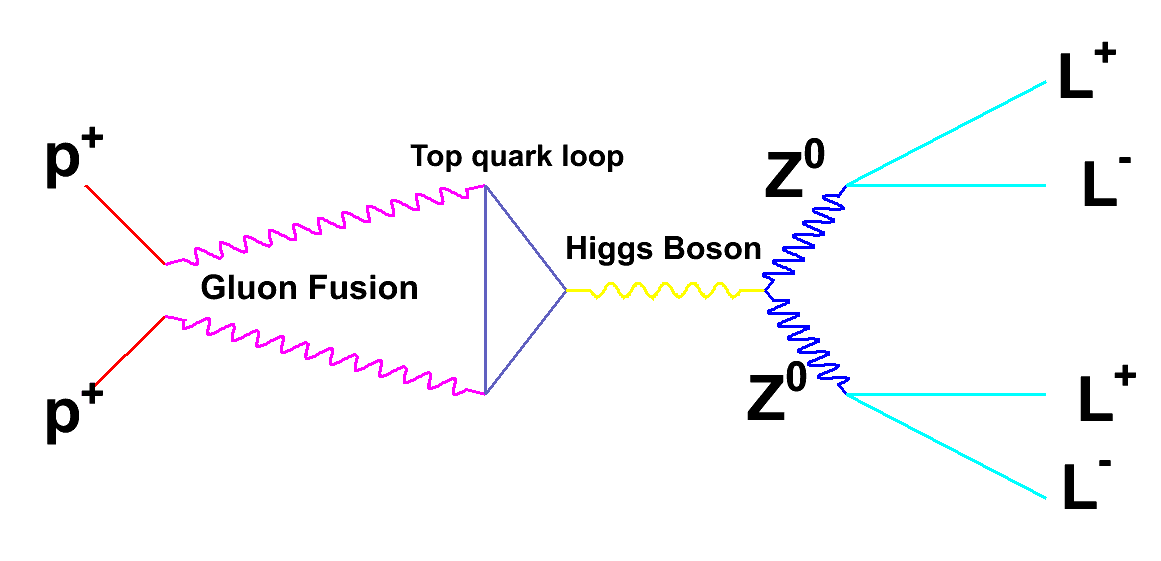

Physical particles can typically decay into a variety of different particles through a variety of different mechanisms. Each of these possible decays is known as a decay mode or channel. One such channel for the Higgs boson is the “golden channel”, whereby the Higgs boson decays into a pair of Z bosons, one of which is in the ground state, which in-turn decay into two pairs of leptons (see Figure 3).

Figure 3:The “golden decay channel” of the Higgs boson, taken from https://

There are a variety of other processes that can lead to the formation of two Z bosons such that we see four leptons. These are termed “background” signals. Figure 4 shows how these separate production modes can sum together with the Higgs production channel to produce our observed signal.

Figure 4:Four-lepton invariant mass distribution in the golden decay channel, taken from https://

Analysis¶

We gain an insight into some of the analysis that was undertaken by the LHC teams by looking at simulated data. This is only a small peek into the work required — most of the difficulty in high energy physics experiments lies in the experimental capture and reconstruction of the data.

There are two kinds of channels within the golden channel that we can look out for. Either, and , or . In the first instance, we produce the following plots:

But, we can also take permutations of events with 2u and 2e:

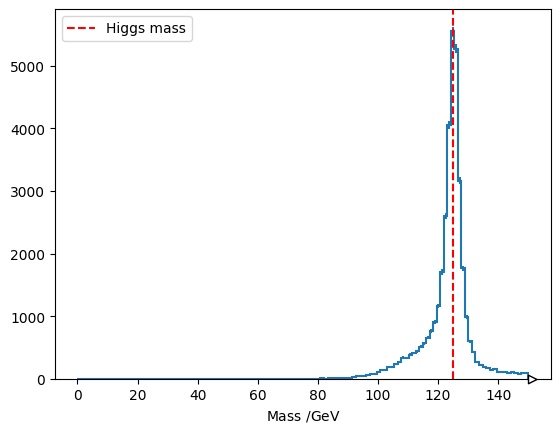

Through the ZZ* decay mode, we know that one of the Z bosons should be in its ground state. We can try to select events that satisfy this constraint via a “cut” that eliminates events failing this criterion:

decay channel of the Higgs boson gated on the ground state of Z.